Perfection is the Enemy of Progress

The 100% Requirements Trap

It's another vacation-time short essay. This one is for those who endlessly find edge cases not covered by the PM’s requirements.

Picture this: Your product manager walks into the engineering standup with a gleam in their eye, ready to pitch the next big feature. Before they finish their second sentence, someone raises their hand. "But what happens when a user has 47 items in their cart and tries to checkout during a leap year while their VPN is routing through Kazakhstan?"

Sounds absurd, right? Yet, in software engineering, we frequently encounter the scenario where engineers refuse to write a single line of code until every microscopic detail is mapped out.

Another victory for engineering rigor—another delay for the roadmap.

The Great Requirements Theater

We've all witnessed this performance. An engineer transforms every product discussion into a doctoral defense, systematically dismantling requirements with the precision of a master debater. Edge cases become weaponized and "what if" scenarios become an art form.

But here's the uncomfortable truth: sometimes that Kazakhstan VPN user represents just 0.01% of your user base, and the three weeks spent "hardening" that scenario could have been spent delivering value to the other 99.99%.

The most insidious part? Everyone believes they're being responsible. The engineer feels they're preventing production disasters. The PM learns to over-specify everything. The engineering manager nods approvingly at their team's "thoroughness."

The Trust Deficit Economy

Why do capable engineers turn into requirement perfectionists?

It's about trust—or rather, its lack. When product teams ask for exact estimates on problems that are inherently uncertain, engineers naturally harden themselves. They search tirelessly for every unlikely loophole and worst-case scenario to protect themselves from future blame.

Sometimes what masquerades as diligence is actually fear—fear of taking responsibility for results. It's psychologically safer to say "the requirements weren't clear enough" than to own a solution that doesn't quite hit the mark. The demand for 100% clarity becomes a sophisticated form of accountability avoidance, ensuring blame always lies elsewhere.

The Opportunity Cost of Perfection

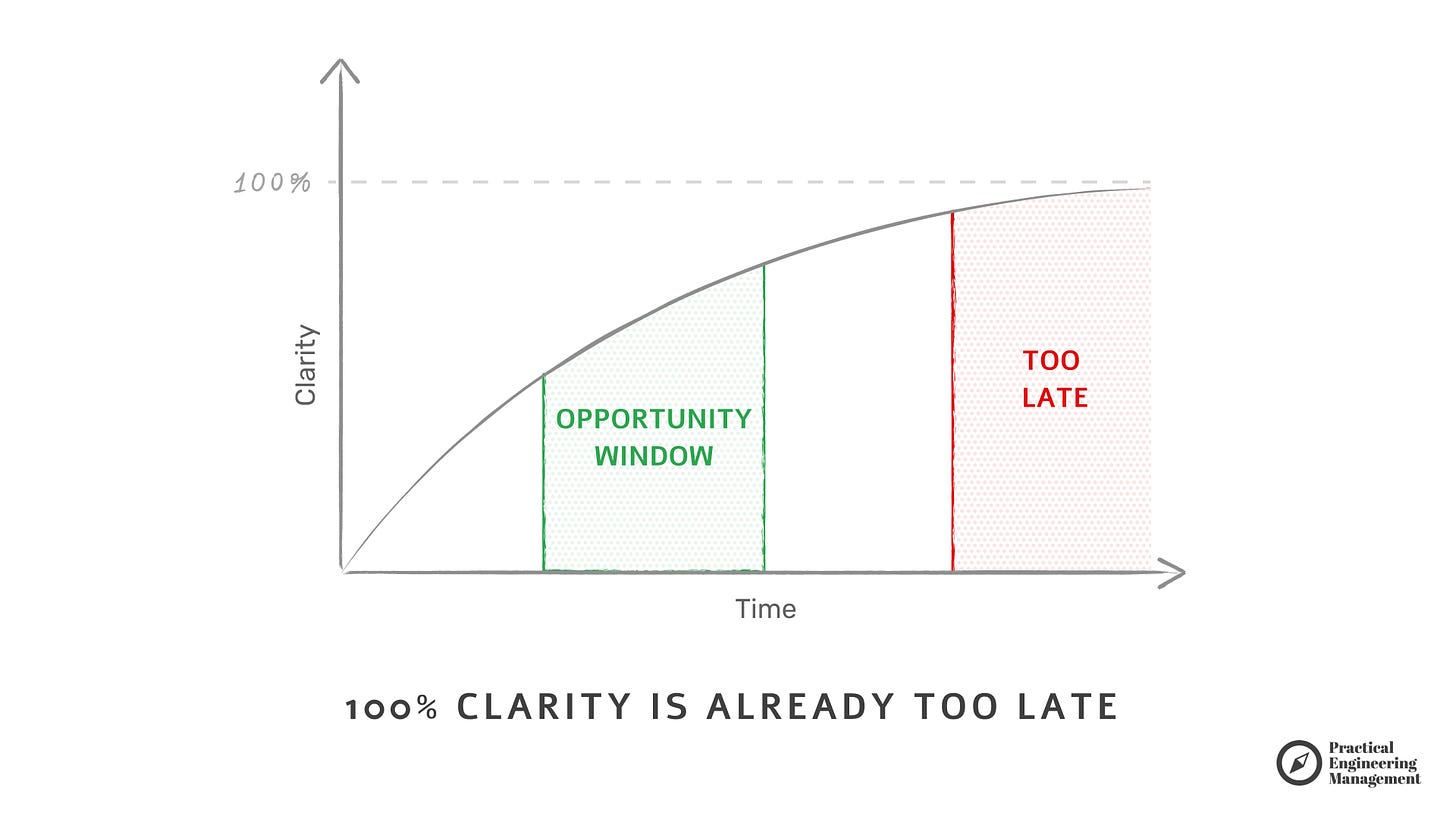

Here's a provocative thought: What if the goal isn't to eliminate uncertainty, but to comfortably operate within it? What if the sweet spot isn't 100% clarity, but somewhere around 50-70%?

Consider this. By the time you achieve perfect clarity, either the market opportunity has shifted, making your solution irrelevant, or the problem is so well-understood that the competitive advantage is minimal.

The companies that move fastest aren't those with exhaustive specifications—they execute effectively despite incomplete information, treating uncertainty not as a bug but as a challenge.

The Courage to Ship Imperfect Solutions

What if engineering teams embraced a different mindset? Instead of asking, "Have we thought of every possible edge case?" they might ask, "What's the minimum viable understanding needed to create maximum viable value?"

Realistically, aiming for 50-70% clarity is healthier. It’s the sweet spot where core direction is clear, but there's enough room for creativity, pivoting, adapting—aaand surprise! engineering solutions.

Great products aren't born from perfect instructions; they're born from navigating ambiguity effectively. Ideal and complete requirements often sabotage timely solutions.

Perfection or Impact?

Could it be that engineers obsessed with perfect clarity aren't simply diligent but afraid? And could leaders inadvertently encourage this fear by prioritizing predictable outcomes over impactful ones?

Reflect on how much clarity your team truly needs—and how much ambiguity they should embrace. Because the future belongs less to those who master every requirement, and more to those who boldly navigate the spaces in between.

If you're willing to explore deeper, consider these provocative questions:

When was the last time your team shipped with only 60% clarity? How did it go?

What would happen if you told your product partners, "Give us the core problem and success metrics—we'll handle the edge cases as we go"?

Are your engineers optimizing to be right or useful?

How many "Kazakhstan VPN" scenarios are you solving for imaginary users?

The goal isn't to eliminate thoughtful engineering—it's to channel thoughtfulness toward impact, not perfection. Great engineering cultures don't avoid uncertainty; they thrive within it.

After all, if you're waiting for 100% clarity, you might end up building the perfect solution for yesterday's problem.

I fully agree with the premise of this article, but (as a professional project manager of several decades) I think you need to include an element of risk analysis.

In other words, what happens if you have missed a requirement?

If the answer is that a single user fails to place an order, that isn't a serious issue.

But if missing functionality could give rise to significant legal action or financial losses, that is much more serious.

I define perfectionism as something relative. In professional fields where everything is done in an amateur way, for example, it can be a huge differentiator. In technical fields, it becomes a form of risk prevention, avoiding bigger problems down the road. I agree that for certain things it’s just unnecessary bureaucracy (and that’s when it hinders growth), but in the right context, it’s necessary.